Welcome back to My Weird Prompts. I am Corn, and I am joined, as always, by my brother.

Herman Poppleberry, at your service. It is good to be here, Corn. Especially since we are tackling a topic that is literally rising up all around us right now. If you look out the window of our studio here in Jerusalem, the skyline is basically a forest of yellow steel cranes.

It really is. And that is actually the perfect backdrop for today’s episode. Our housemate Daniel sent in a prompt that hits very close to home—literally. He was asking about the invisible forces that shape our cities. Not just the bricks and mortar, but the planning regulations, the zoning codes, and the massive bureaucracy that determine what gets built, why it gets built, and who it is actually for.

It is a fascinating angle because most people see a construction site and think about the architect or the developer. But the real "architect" of a city is often a set of codes and a committee sitting in a government office years before the first shovel hits the ground. Daniel was specifically curious about how Israel's system compares to other models and whether we can move away from this high-revenue, developer-led approach toward something more human-centered.

It is a big question. We live here in Jerusalem, and you cannot walk two blocks without seeing a massive crane or a "Pinui Binui" sign, which is the urban renewal program here. But it often feels like the "human" part of the city is an afterthought. It is all about maximizing units or revenue. So, Herman, let us start with the "why." Why does the planning system in Israel feel so rigid and bureaucratic compared to what we see in other parts of the world?

To understand that, we have to look at how land is owned and managed here. In many countries, like the United States or parts of Europe, land ownership is highly fragmented among millions of private individuals. In Israel, the state, through the Israel Land Authority, or the ILA, owns about ninety-three percent of the land. That is a massive outlier among developed nations.

Ninety-three percent? That is almost the entire country. How does that even work in practice? Do people not actually own their homes?

Technically, most people are on a ninety-eight-year lease. The state is the ultimate landlord. And because the state owns the land, the planning process is deeply centralized. You have the National Planning and Building Council at the top, followed by six regional committees, and then the local committees. It is a top-down hierarchy. Every major project has to climb this ladder of approvals. This creates a bottleneck effect where getting a permit can take years—sometimes even a decade for large-scale developments.

And I imagine that bottleneck favors the big players. If you are a small community group or a boutique developer who wants to build something unique or human-scaled, you probably do not have the legal team or the capital to wait ten years for a permit.

You hit the nail on the head. This is what leads to that "sugar high" of high-revenue projects. Because the process is so slow and expensive, the system naturally gravitates toward projects that can "absorb" those costs. That means massive high-rises, luxury apartments, and large-scale commercial centers. These projects generate huge amounts of "betterment taxes" and permit fees for the municipalities.

Wait, explain that "betterment tax" part. That sounds like a key piece of the puzzle.

It is called "Hetel Hashbacha." Basically, if the city grants you a permit to build something more valuable than what was there before—like turning a two-story house into a twenty-story tower—you have to pay the city fifty percent of that increased value. It is a massive source of income for local governments. But it creates a perverse incentive: the city wants the biggest, most expensive projects possible because that is how they fill their coffers.

So the city is essentially a partner in the developer's profit. But what about the "Arnona"—the municipal property tax? I have heard that is part of the problem too.

Oh, it is the "original sin" of Israeli urban planning. In Israel, residential property tax is actually a net loss for a city. The cost of providing services to a resident—schools, garbage collection, welfare—is higher than the tax that resident pays. However, commercial property tax is a massive profit. So, every mayor in Israel is incentivized to build more office towers and fewer family apartments. If they build too much housing, the city goes bankrupt. If they build a massive tech park, the city gets rich.

That explains why we see so many "mixed-use" projects that are ninety percent office space and ten percent tiny apartments. It is not what people need; it is what the municipal spreadsheet requires. But Daniel asked about other models. Where is this being done differently?

Japan is the gold standard for many urban planners when it comes to flexible, human-centered zoning. In most of the West, we use what is called "Euclidean Zoning," named after a court case in Euclid, Ohio, back in nineteen twenty-six. It is very rigid. This area is residential, that area is industrial, and this area is commercial. Never the twain shall meet.

Right, which is why you end up with those "food deserts" or suburbs where you have to drive twenty minutes just to buy a carton of milk.

Precisely. Japan does it differently. They have a national zoning code with only about twelve zones, and they are "inclusive" rather than "exclusive." They use a "cascade" system.

A cascade? Like a waterfall?

Exactly. Think of it this way: the most restrictive zone is "Low-Rise Residential." In that zone, you can build a house, but you can also have a small grocery store or a home-based office. As you move to the next zone, say "Medium-Rise Residential," everything allowed in the first zone is still allowed, plus more intense uses like larger shops or small factories. By the time you get to the "Commercial" zone, you can build almost anything—including housing. In the West, we often ban housing in commercial zones. In Japan, they realize that having people live near where they shop and work is actually a good thing.

So, in Tokyo, if I want to open a tiny bakery on the ground floor of my house, I do not need to go to a three-year public hearing to change the zoning?

In most cases, no. It is allowed "by right." That is a key phrase in planning. It means if your project fits the pre-defined rules, the government must give you the permit. It takes the "politics" out of the planning. It lowers the barrier to entry for smaller projects. It is why Tokyo, despite being one of the most populous cities on earth, remains surprisingly affordable compared to London or New York. They just keep building, and they build at a scale that fits the neighborhood.

"By right" sounds like a dream compared to the "By permission" system we have here. But why can't we just "import" that? What is the friction?

One major layer is the "NIMBY" factor—Not In My Backyard. In many Western systems, the discretionary permit process is a weapon used by existing homeowners to block new development. They worry about property values, shadows, or traffic. In Japan, because the zoning is national, local neighbors have much less power to block a project that meets the code. It is a trade-off between local control and systemic efficiency.

That is a tough one. Daniel was asking how we can let "communities" determine what gets built. If you take away their power to block things, aren't you moving away from community control? Or is there a different way for a community to be "in the driving seat" without just being an "obstructionist force"?

This is where we get into "Form-Based Codes" versus "Use-Based Codes." This movement has been gaining steam in places like Miami and parts of Europe. Instead of the city telling you what goes inside the building—like "this must be a shoe store"—the code focuses on how the building relates to the street.

So, things like the height of the ground floor, how much glass is on the storefront, or where the entrance is located?

Exactly. The goal is to ensure the building contributes to a high-quality "public realm." If the building creates a nice, walkable environment with shade and active storefronts, the city cares much less about whether the second floor is an office or an apartment. This allows the community to define the "character" of their streets through the physical form, while allowing the market and the residents to decide the actual "use" of the space.

I like that. It feels more like setting the "rules of the game" rather than trying to predict the outcome of every single move. But let us talk about the "housing as a human need" part of Daniel's prompt. Even with flexible zoning, you still have the issue of affordability. In Israel, the prices are astronomical. Is there a planning model that prioritizes people over profit margins?

We have to look at Vienna. The "Vienna Model" is legendary. About sixty percent of the population in Vienna lives in social housing. But it is not the "social housing" we often think of in the United States, which is often stigmatized. In Vienna, social housing is high-quality, architecturally diverse, and integrated into every neighborhood.

How do they pull that off? Especially now, in February twenty-twenty-six, when interest rates and construction costs are still high globally?

It is a long-term commitment. The city owns a lot of land, much like Israel, but instead of selling it to the highest bidder to maximize revenue, they use "Limited Profit Housing Associations." These are private organizations that receive low-interest loans and land from the city. In exchange, they agree to cap their rents and reinvest any profits back into building more housing.

So the goal isn't a "sugar high" of tax revenue, but a "long-term stability" of the workforce.

Exactly. And the planning process there is very collaborative. When a new area is developed, like the "Seestadt Aspern" project, the city holds competitions where developers are judged not just on price, but on social sustainability, ecological impact, and architectural quality. The community is involved in these "thematic competitions." It shifts the incentive from "how many units can I cram in" to "how well does this project serve the people who will live there."

That sounds incredible, but it also sounds like it requires a level of trust in government that might be lacking here. In Israel, there is often a feeling that the bureaucracy is an adversary you have to defeat. How do we bridge that gap?

One way is through "Tactical Urbanism" and "Participatory Budgeting." These are ways to let communities "beta test" changes to their urban space before they become permanent laws. Think about the way some cities turned parking spaces into "parklets" during the pandemic.

Right, and many of those changes became permanent because people realized they liked having a place to sit more than they liked having one extra car parked on the street.

Exactly. It is a "bottom-up" approach to planning. Instead of a ten-year master plan, you do a six-month pilot project. You collect data. You see how people actually use the space. If it works, you bake it into the code. This gives the community a tangible way to shape their environment without getting lost in "Permit Purgatory."

I want to dig a bit deeper into the Israeli context specifically. We have this program called "Tama Thirty-Eight," which was originally designed to earthquake-proof old buildings by allowing developers to add extra floors. But as of right now, in early twenty-twenty-six, it is in a very strange place, isn't it?

It is in its "final sprint." Tama Thirty-Eight officially expired in most major cities like Tel Aviv and Bat Yam back in August twenty-twenty-four. But in about eighteen other local councils, including parts of Jerusalem, it was extended until May twenty-twenty-six. So we are currently in this frantic window where developers are racing to file applications before the deadline.

And that "race" feels chaotic. It often feels like it is tearing the "soul" out of neighborhoods. You get these ultra-modern additions on top of charming old stone buildings, and the infrastructure—the sewers, the schools, the sidewalks—stays exactly the same.

That is the "Infrastructure Lag." Tama Thirty-Eight is a classic example of "Incentive-Based Planning" gone wrong. The government wanted a certain outcome—earthquake safety—but they didn't want to pay for it. So they "sold" the air rights to developers. The problem is that a developer's incentive is to maximize the sellable area, not to ensure there is enough room in the local kindergarten for the thirty new families moving in.

And because it is building-by-building, there is no holistic vision for the street. You might have five buildings in a row all doing projects, but they aren't coordinated. The sidewalk is still two feet wide, and now there are fifty more cars trying to park there.

This is why the replacement for Tama Thirty-Eight—often called the "Shaked Plan" or the "Alternative to Tama"—is trying to move toward "Complex-wide" planning. Instead of one building, you look at a whole block. You say, "Okay, we will add density, but we will also carve out space for a small public park and a daycare center on the ground floor."

That sounds better on paper, but it still feels like it is driven by the need for more units above all else. What about the "Superblocks" model? I know Daniel mentioned that.

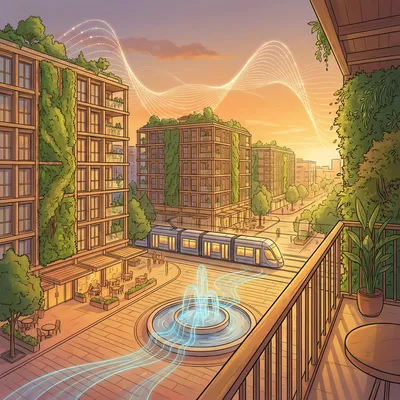

Barcelona's Superblocks are the dream. They took a grid of nine city blocks and restricted through-traffic to the perimeter. The interior streets became "shared spaces" for pedestrians and bikes. It didn't require tearing down buildings; it just required a change in how the "space between the buildings" was managed.

I read that the expansion of the Superblocks was actually paused recently in Barcelona due to some political shifts.

It was. And that is the reality of urban planning—it is always a battle between different visions of the city. But the data from the existing Superblocks is undeniable. Air pollution dropped, noise levels plummeted, and local business activity actually went up because people were walking instead of driving past.

See, that feels like a "human-centered" move. It prioritizes the quality of life for the people already living there. But I can hear the counter-argument: "We have a housing crisis! We need more units! We can't afford to lose parking!" How do you balance the desperate need for more housing with the need for that housing to actually be livable?

It is a false dichotomy, Corn. You can have density without "hostility." Look at Paris. It is one of the densest cities in the world, but it is also one of the most walkable. Most of Paris is six to eight stories tall. It is what we call "Mid-Rise Density" or the "Missing Middle."

We have talked about this before—the "Missing Middle." Why is it so hard to build that here?

Because the planning system is currently set up for "Extremes." You either have low-density villas or high-density towers. There is very little of that "sweet spot" in the middle. Towers are expensive to build and maintain, and they often create "dead zones" at the street level because they are set back behind lobbies and parking ramps.

So, if we want to move toward a more human-centered city, the planning code needs to explicitly encourage that "six-to-eight story" model. But here is the catch: in Israel, the land is so expensive that developers claim they must build forty stories just to break even. Is that true?

It is a bit of both. Because the state "auctions" the land to the highest bidder, the land price is driven up by the expectation of high density. If a developer pays a hundred million shekels for a plot of land, they do need to build a tower to make a profit. But if the city changed the rules and said, "In this neighborhood, you can only build eight stories, but you can build them faster and with fewer taxes," the land price would eventually adjust downward to reflect that reality.

So the high land prices are a result of the planning system, not just a natural law of physics.

Precisely. The planning system creates the value of the land. If you change the "permitted use," you change the "economic reality." If we want affordable, human-scaled cities, we have to stop using land auctions as a way to fill the national treasury. We have to start treating land as a platform for community-building rather than a commodity for extraction.

That is a profound shift in mindset. I wonder if there are examples of "Community Land Trusts" that could work here. For those who don't know, a Community Land Trust, or CLT, is where a non-profit owns the land, and individuals own the houses on top of it. It takes the "speculative value" of the land out of the equation.

There are thousands of them. The Champlain Housing Trust in Burlington, Vermont, is a great example. They have over three thousand homes. If the land is owned by a trust whose mission is "community stability," they won't sell it to a developer just because the market is hot. They will keep the rents low so that teachers, nurses, and artists can actually afford to live in the city.

Imagine if the Israel Land Authority carved out ten percent of its holdings for Community Land Trusts. That would be a game-changer. It would allow for the kind of "community-driven" projects Daniel was asking about. People could come together to build "co-housing" projects where they share a kitchen or a garden, focusing on social connection rather than resale value.

And that is where the real "innovation" happens. When you give people the tools to shape their own environment, they come up with solutions that a centralized planning committee would never think of. They build what they actually need—childcare centers, workshops, shared libraries—rather than what a spreadsheet says will generate the highest "Internal Rate of Return."

I think about the "Fifteen-Minute City" concept. The idea that everything you need for daily life should be within a fifteen-minute walk or bike ride. To achieve that, you need a planning code that is incredibly flexible. You can't have "zones" that are three miles wide. You need "micro-mixing."

And you need "Active Frontages." One of the biggest problems in modern planning is the "Blank Wall." You walk past a new luxury building, and for a hundred yards, all you see is a concrete wall or a tinted-glass lobby. It kills the street life. A human-centered code would mandate that every building has "small-grain" commercial spaces at the bottom. Not one giant supermarket, but six small shops.

Because six small shops mean six different business owners, six different reasons for people to stop, and six different opportunities for a "chance encounter" with a neighbor. That is what makes a city feel like a community rather than just a collection of storage units for humans.

Exactly. It is about "Social Friction." We want a city that encourages people to bump into each other. The current bureaucratic model in Israel, which favors massive, "self-contained" developments, actually reduces social friction. People drive into their underground parking, take the elevator to their floor, and never have to interact with the "city" at all.

It is a "vertical suburbia." And it is incredibly isolating. So, if we were to draft a "Manifesto for a Human-Centered Jerusalem," what would be the top three items?

First, I would say "Eliminate Discretionary Zoning for the Missing Middle." If you want to build a six-story building with shops on the bottom and apartments on top, and it meets the safety codes, you should get your permit in thirty days. No committees, no hearings. Just build it.

I love that. "By-right" development for human-scale buildings. What is number two?

"End the Land Auction Arms Race." The state should stop selling land to the highest bidder. Instead, land should be leased to projects based on their "Social Score." How much affordable housing are you providing? How much public space are you creating? The "price" of the land should be the last thing on the list.

That would definitely cool down the speculation. And number three?

"Mandatory Participatory Design for Public Spaces." Every new neighborhood or major urban renewal project should have a "Community Design Studio" on-site for a year before the plans are finalized. Not a "public hearing" where people shout at each other for two hours, but an actual collaborative process where residents work with architects to map out where the paths should go and where the trees should be planted.

It is about moving from "Planning FOR people" to "Planning WITH people." It sounds so simple, yet it is so far from our current reality. But we are seeing small cracks in the wall. There are some local councils here in Israel that are starting to experiment with "urbanism units" that are more focused on the street level.

There is a growing movement of "Urban Activism" here. People are realizing that they don't have to just accept whatever the "National Committee" decides. They are fighting for bike lanes, they are planting "guerrilla gardens," and they are demanding better public transit. Even with the Arnona hikes we saw this year—Jerusalem saw some massive increases for small apartments—people are starting to ask, "What am I actually getting for this money? Is my street becoming more livable, or just more expensive?"

It feels like we are at a tipping point. The "tower-and-car" model is clearly failing. It's creating traffic gridlock, social isolation, and an affordability crisis that is driving young people out of the cities. The "weird" thing is that the solutions aren't actually that futuristic. They are often just "re-learning" the lessons of the great cities of the past.

It is "Ancient Wisdom" meets "Modern Technology." We have the data to show that walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods are healthier, more economically productive, and more resilient. We just need the political will to change the "software"—the codes and the laws—to match the "hardware" of our human needs.

This has been a deep dive, Herman. I feel like I look at the construction sites outside our window a bit differently now. It is not just a building; it is the physical manifestation of a set of rules and incentives.

And those rules are not written in stone, Corn. They were written by people, and they can be rewritten by people. That is the most important thing for listeners to remember. The way our cities look is a choice.

Well, if you have been enjoying this exploration of the "unseen forces" that shape our world, we would really appreciate it if you could leave us a review on your podcast app or on Spotify. It genuinely helps other curious minds find the show.

It really does. And if you want to see the "RSS feed" or get in touch with us, you can head over to our website at myweirdprompts.com. We love hearing from you, and who knows? Your question might be the spark for our next deep dive.

Thanks to Daniel for sending in this prompt. It definitely gave us a lot to chew on during our next walk through the neighborhood.

Definitely. I am already looking at that empty lot on the corner and imagining an eight-story "co-housing" project with a bakery on the ground floor.

One can dream, Herman. One can dream. Thanks for listening to My Weird Prompts. We will see you next time.

Goodbye everyone! Stay curious.