Hey everyone, welcome back to My Weird Prompts. I am Corn, and I am sitting here in our living room in Jerusalem with my brother.

Herman Poppleberry, at your service. It is a beautiful day outside, Corn, although if I look out the window toward the entrance of the city, the view is mostly yellow cranes and half-finished concrete skeletons.

Exactly what Daniel was talking about in his prompt this morning. Our housemate Daniel sent us a voice note about the high-rise explosion happening right here in Jerusalem. He is calling it a mess, and honestly, it is hard to disagree when you are trying to navigate the traffic around the central bus station.

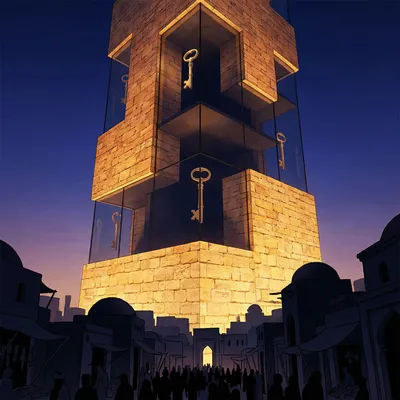

It is a massive shift. For decades, Jerusalem was defined by its low-rise, stone-clad skyline. Now, it feels like we are watching a vertical revolution in real-time. We are talking about the Jerusalem Gateway project, which is planning a major cluster of high-rise towers, some reaching around forty stories, right at the entrance to the city. Daniel raised some really sharp points about the social and aesthetic costs of this transformation, and I have been digging into the latest urban planning papers and the recent tax changes for 2026 all morning.

It is funny, because we have touched on urban issues before, like back in episode one hundred and ninety-seven when we talked about home leaks and infrastructure, but this is on a much grander scale. This is about the soul of a city versus the demands of a modern economy. Let us start with that aesthetic point Daniel made. Jerusalem has this very specific, almost sacred look. The limestone, the hills, the way the light hits the city at sunset. Does a forty-story glass tower just ruin that?

That is the big question. Historically, British Mandate-era regulations required all buildings in Jerusalem to be faced with Jerusalem stone, and that requirement is still effectively on the books. But when you apply that to a skyscraper, you get this strange hybrid. It is not really a traditional Jerusalem building, and it is not a sleek modern skyscraper either. Some architects call it a stone-cladded monolith.

It feels a bit like a compromise that satisfies no one. You have these massive structures that are supposed to look ancient because of the stone, but their scale is completely alien to the surrounding neighborhoods. I was walking through Nachlaot the other day, which is full of these tiny, one-hundred-year-old stone houses with courtyards, and then you look up and there is this giant tower looming over everything. It creates this sense of being dwarfed in your own neighborhood.

And that scale issue is not just about looks. It is about shadows and wind tunnels. When you build that high in a city that was designed for horse and carriage or small buses, you change the micro-climate of the street. But from a planning perspective, the city argues they have no choice. Jerusalem is surrounded by green belts and sensitive historical sites. You cannot sprawl outward forever without destroying the Jerusalem Forest or building on top of archaeological sites. So, the only way is up.

I get the logic of density, Herman. I really do. In theory, building up should make housing more affordable by increasing supply, right? But that brings us to Daniel's second point, which is the one that really stings for people living here. These are not affordable apartments for young couples or local families. These are luxury towers.

Right. The Dirot Refaim, or Ghost Apartments. This is a phenomenon where wealthy members of the diaspora buy these high-end units as vacation homes. They want a piece of the Holy City for Passover or Sukkot. But the rest of the year? The shutters are down. The lights are off.

It is eerie. You walk past some of these new developments at night and eighty percent of the windows are dark. Meanwhile, the rental prices in the surrounding areas are skyrocketing because the land value has been pushed up by these luxury projects. It feels like a paradox. We are building more than ever, but the people who actually live and work in the city are being priced out.

There is a term for this in urban sociology called investment-led displacement. The housing is treated as a financial asset rather than a place to live. When a building is mostly empty, it also kills the local economy on that block. If no one is living there, the local grocery store and the small cafe lose their customer base. You end up with these dead zones in the middle of a vibrant city.

And the resentment Daniel mentioned is very real. Imagine you are a teacher or a nurse living in a cramped apartment in Kiryat HaYovel, and you spend an hour in traffic every day because of construction on a new tower that you could never dream of affording. You see the noise, you hear the dust, and the end result is a building that stays dark ten months a year. It feels like the city is being sold off piece by piece.

It is a classic case of the city serving a global elite rather than its local citizens. But Jerusalem is not alone in this. This is a problem in London, Vancouver, and Paris. The question is, how do you manage it? Daniel asked about social policy and how other governments handle this. I found some fascinating examples of how cities are fighting back.

I am curious about that. Because it feels like once the developers have the permits, the momentum is almost impossible to stop. What can a city actually do?

Well, look at Vancouver. They have a formal Empty Homes Tax. In recent years the rate has been set at a few percent of the property's assessed value, with declarations typically due around the start of the following year. On top of that, the provincial government charges a separate Speculation and Vacancy Tax that imposes higher annual rates on many foreign owners than on most local residents.

A yearly tax of a few percent of the value of a luxury apartment? That is a massive amount of money. Does it actually work?

It has had a measurable impact. Vancouver reported that the number of vacant properties dropped significantly in the first few years. More importantly, it generated hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue that the city specifically earmarked for affordable housing initiatives. So even if the wealthy owner keeps the apartment empty, they are essentially subsidizing a home for someone else.

That seems like a fair trade-off. What about Jerusalem? I know there has been talk of a double Arnona tax. Has that actually been implemented?

The Israeli government did pass regulations allowing municipalities to charge double the property tax on apartments that are defined as empty for at least nine months of the year. Jerusalem has used this, but the problem is the definition of empty. It is often based on water or electricity usage. If an owner leaves a few lights on a timer or has a management company flush the toilets once a week, it can be hard to prove the place is vacant. However, as of early twenty-twenty-six, Israel is rolling out a major Arnona reform that is expected to significantly raise property tax bills for many apartments in Jerusalem, with the sharpest increases likely to fall on some older units. It is a huge shakeup.

So it becomes a game of cat and mouse. It seems like you need a more robust system, something like the Vancouver model where the burden of proof is on the owner. What about Europe?

London uses what they call the threshold approach. Before a developer gets permission for a high-rise, they are encouraged to provide at least thirty-five percent affordable housing. If they do not meet that, they have to go through a rigorous viability assessment to prove why they cannot. And in Paris, they have actually gone the other way. As part of their new bioclimatic urban plan adopted in the mid-twenty-twenties, they have tightened height limits so that most new buildings in much of the historic core are capped at roughly thirty-seven meters, which is about twelve stories. They decided that towers just do not fit the historic core.

That is bold. It forces the market to adapt to the city, rather than the city adapting to the market. Jerusalem could definitely learn from that. We have a huge issue with apartments being turned into unofficial hotels, which further depletes the supply for residents.

Exactly. And Barcelona has a special urban plan for tourist accommodation where they have essentially mapped the city into zones. In the most crowded areas, they do not allow any new tourist licenses at all. They are trying to actively shrink the tourist footprint to make room for locals.

It feels like these cities have realized that their primary asset is not the tourists, but the living culture of the city itself. If you lose the locals, the tourists will eventually stop coming because the city will have lost its charm. It becomes a theme park version of itself.

That is the danger for Jerusalem. People come here for the history and the atmosphere. If that atmosphere is replaced by generic glass towers and empty streets, the very thing that makes the city valuable disappears. It is a form of economic cannibalism.

So, if we were the mayors of Jerusalem for a day, what would we do? Beyond the double property tax, how do we fix this mess?

I think the first step is a mandatory percentage of truly affordable, long-term rental units in every new development. Not just for sale, but for rent, managed by the city or a non-profit. This ensures that young families and key workers, like teachers and nurses, actually live in the center of town.

I would also add a requirement for public amenities. If you are building a forty-story tower, the first three floors should be a public library, a community center, or a subsidized space for local artists. Make the building a resource for the neighborhood, not just a fortress for the wealthy.

And we need to be much more aggressive about the empty homes tax. We need a system that actually works. If an apartment is empty for more than nine months a year, the tax should be high enough that it is no longer a viable passive investment.

It is about changing the incentive structure. Right now, the system is designed to favor the developer and the high-end investor. We need to tilt it back toward the resident. I also think we need to be more selective about where these towers go. Do they really need to be right next to the Old City?

That was the original plan for the Jerusalem Gateway project. The idea was to concentrate the high-rises there, near the train station, to minimize the impact on the rest of the city. But the problem is that once the height limits are broken in one place, every developer wants an exception for their project in another neighborhood. It is a slippery slope.

It really is. And once a tower is built, it is there for a hundred years. You cannot undo it easily. It is a permanent change to the landscape. I think that is why the controversy is so heated. It feels like a loss of control for the people who live here.

There is also a psychological aspect to it. Jerusalem is a city of memory. When you change the physical environment so drastically, you disrupt people's connection to their own history. It is a form of architectural gaslighting.

That is exactly what Daniel said. He felt like he stepped into a computer game. The familiar landmarks are gone, replaced by these generic structures. It is a very disorienting experience.

I will say one thing in defense of density, though. From an environmental perspective, building up is better than building out. If we want to preserve the hills and forests around Jerusalem, we have to live closer together. But density without community is just a warehouse for people. We need to figure out how to do high-rise living that actually fosters social connection.

That is the challenge. How do you build a vertical neighborhood? Maybe the answer is in the design. More shared spaces, more communal gardens, more ways for people to interact. But that costs money and takes up space that developers would rather sell as luxury square footage.

It requires strong regulation. The market will never do that on its own. The market wants to maximize profit per square foot. The city's job is to protect the public interest, which includes things like social cohesion and historical character.

It feels like the balance is currently skewed way too far toward the market. But as we have seen in cities like Vancouver and Barcelona, it is possible to fight back. It just takes political will and a clear vision for what the city should be.

And it takes residents who are willing to speak up. The backlash in Jerusalem is growing. People are starting to realize that the skyline belongs to everyone, not just the people who can afford the penthouse.

I hope they listen. Because I would hate to see Jerusalem become a city of ghosts. It is too vibrant and too important for that.

Well said, Corn. I think we have covered a lot of ground here. From the aesthetics of stone cladding to the economics of empty homes and the global policies that could help.

It is a complex issue, and there are no easy answers, but talking about it is the first step. I am glad Daniel sent this in. It is something we see every day but do not always take the time to analyze.

Exactly. It is the background noise of our lives, but it is actually the story of our city's future.

Before we wrap up, I want to remind everyone that if you are enjoying these deep dives, please leave us a review on your podcast app or on Spotify. It really helps other curious minds find the show.

It really does. And you can find all our past episodes at our website, myweirdprompts.com. There is also a contact form there if you want to send us a prompt of your own.

We love hearing from you guys. And a big thanks to our housemate Daniel for this one. It definitely gave us a lot to think about on our walk to the grocery store later.

Just watch out for the construction trucks, Corn. They are everywhere.

I will. Alright, that is it for this episode of My Weird Prompts. Thanks for listening, and we will talk to you next week.

Until next time, keep asking those weird questions.

Take care, everyone. Bye!

Bye for now!

So, Herman, do you think we will ever live in one of those towers?

Honestly, Corn? I think I would miss the garden too much. And the stairs. A donkey needs a bit of a workout, you know?

Fair point. I am happy right where we are. Let us go see if Daniel wants to grab some hummus.

Sounds like a plan. Let's go.

This has been My Weird Prompts. We are available on Spotify and at myweirdprompts.com. Thanks for being part of the collaboration.

See you in the next one!